Warm nights

26 November 2010

People often ask whether the weather in Hong Kong is getting hotter and hotter. Well, it is. But not in the sense that we normally associate hot weather with.

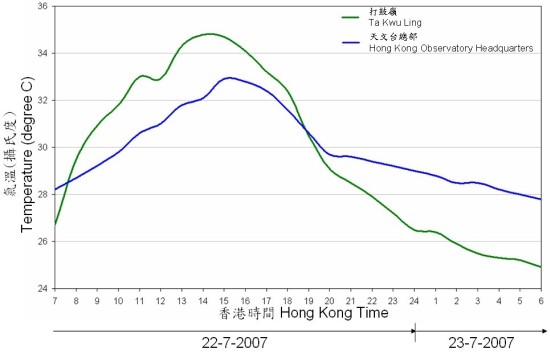

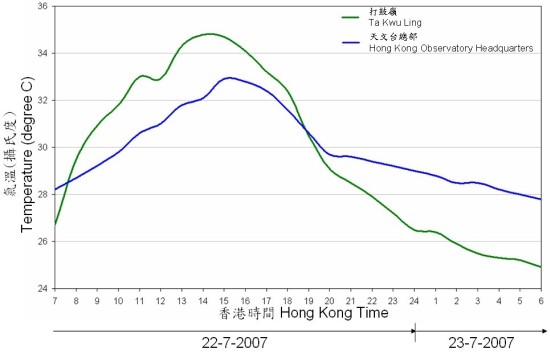

The high degree of urbanization in Hong Kong means that during the day, some of the heat particularly that from the Sun becomes absorbed by buildings, roads and other structures. The result is that daytime temperatures in the city are normally lower than those in rural areas. For instance, day time the temperatures at the Hong Kong Observatory (in the city centre in Kowloon) are often a couple of degrees lower than that at the New Territories, e.g. Ta Kwu Ling.

At night, the situation is reversed. The heat stored in buildings etc. is released back to the air. This makes the nighttime temperature in the city higher than that in rural areas.

Figure 1Temperature difference between city and countryside in a typical summer day in Hong Kong

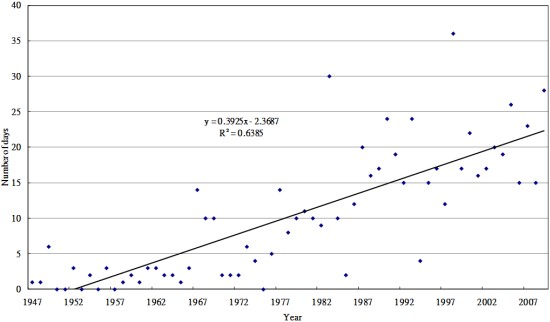

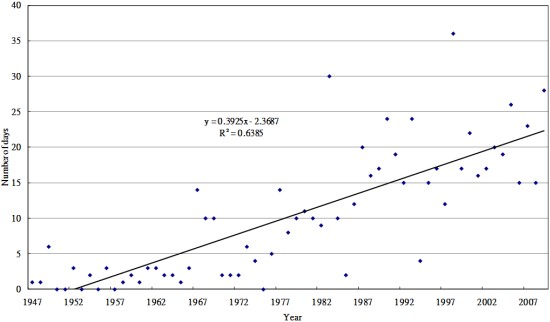

Recently there was a "No air-conditioning day" campaign in Hong Kong. I asked my colleague to compute the number of 'warm nights' at the Observatory for the past 60 years, i.e. after the Second World War. A warm night means that the minimum temperature that night reaches 28 degrees or above. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2Number of warm nights at the Hong Kong Observatory, 1947-2009

The diagram tells us that, on average, the number of warm nights has increased from practically none during the 1950s to more than 20 by the end of the 2000s.

In terms of warm nights, the situation at Ta Kwu Ling is entirely different. The station there is located in an area which remains largely rural to this day. There was no warm night over the past 10 years from 2000 to 2009, except for 2004 which had only one warm night. On this account, therefore, Ta Kwu Ling is quite a habitable place. A fan is probably all it takes for cooling during nighttime.

What is going to happen in the city in 10 years' time? Our computations based on an average of possible emission scenarios (ranging from 'business as usual' to aggressive 'do what we can') tell us that by 2020, the number of warm nights will more than double, to 55 per year. The number of hot days, that is, those days with daytime temperatures reaching 33 degrees or above, will also double from 13 to 27 per year.

Hotter weather means that, without a fundamental change in our lifestyle, more fossil-based energy will be used for cooling. This inevitably will exacerbate the release of carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas, into the air. This in turn will bring further warming, feeding a vicious circle.

B.Y. Lee

Reference

United Nations IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 4th Assessment Report (2007)

The high degree of urbanization in Hong Kong means that during the day, some of the heat particularly that from the Sun becomes absorbed by buildings, roads and other structures. The result is that daytime temperatures in the city are normally lower than those in rural areas. For instance, day time the temperatures at the Hong Kong Observatory (in the city centre in Kowloon) are often a couple of degrees lower than that at the New Territories, e.g. Ta Kwu Ling.

At night, the situation is reversed. The heat stored in buildings etc. is released back to the air. This makes the nighttime temperature in the city higher than that in rural areas.

Figure 1Temperature difference between city and countryside in a typical summer day in Hong Kong

Recently there was a "No air-conditioning day" campaign in Hong Kong. I asked my colleague to compute the number of 'warm nights' at the Observatory for the past 60 years, i.e. after the Second World War. A warm night means that the minimum temperature that night reaches 28 degrees or above. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2Number of warm nights at the Hong Kong Observatory, 1947-2009

The diagram tells us that, on average, the number of warm nights has increased from practically none during the 1950s to more than 20 by the end of the 2000s.

In terms of warm nights, the situation at Ta Kwu Ling is entirely different. The station there is located in an area which remains largely rural to this day. There was no warm night over the past 10 years from 2000 to 2009, except for 2004 which had only one warm night. On this account, therefore, Ta Kwu Ling is quite a habitable place. A fan is probably all it takes for cooling during nighttime.

What is going to happen in the city in 10 years' time? Our computations based on an average of possible emission scenarios (ranging from 'business as usual' to aggressive 'do what we can') tell us that by 2020, the number of warm nights will more than double, to 55 per year. The number of hot days, that is, those days with daytime temperatures reaching 33 degrees or above, will also double from 13 to 27 per year.

Hotter weather means that, without a fundamental change in our lifestyle, more fossil-based energy will be used for cooling. This inevitably will exacerbate the release of carbon dioxide, the major greenhouse gas, into the air. This in turn will bring further warming, feeding a vicious circle.

B.Y. Lee

Reference

United Nations IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 4th Assessment Report (2007)