Earthquake and Tsunami Knowledge We Need to Know

27 June 2025

Bowie YP Chan, Wilson WS Chan

As summer approaches, parents may plan to take their children on a trip. To ensure a safe and enjoyable journey, understanding disaster preparedness and response measures is crucial. Earthquakes and tsunamis are geological related natural hazards. Here, we would like to share three key areas of knowledge about these hazards, including their risks, predictability, and practical measures for disaster preparedness, prevention and response.

1. Earthquake and Tsunami Risks

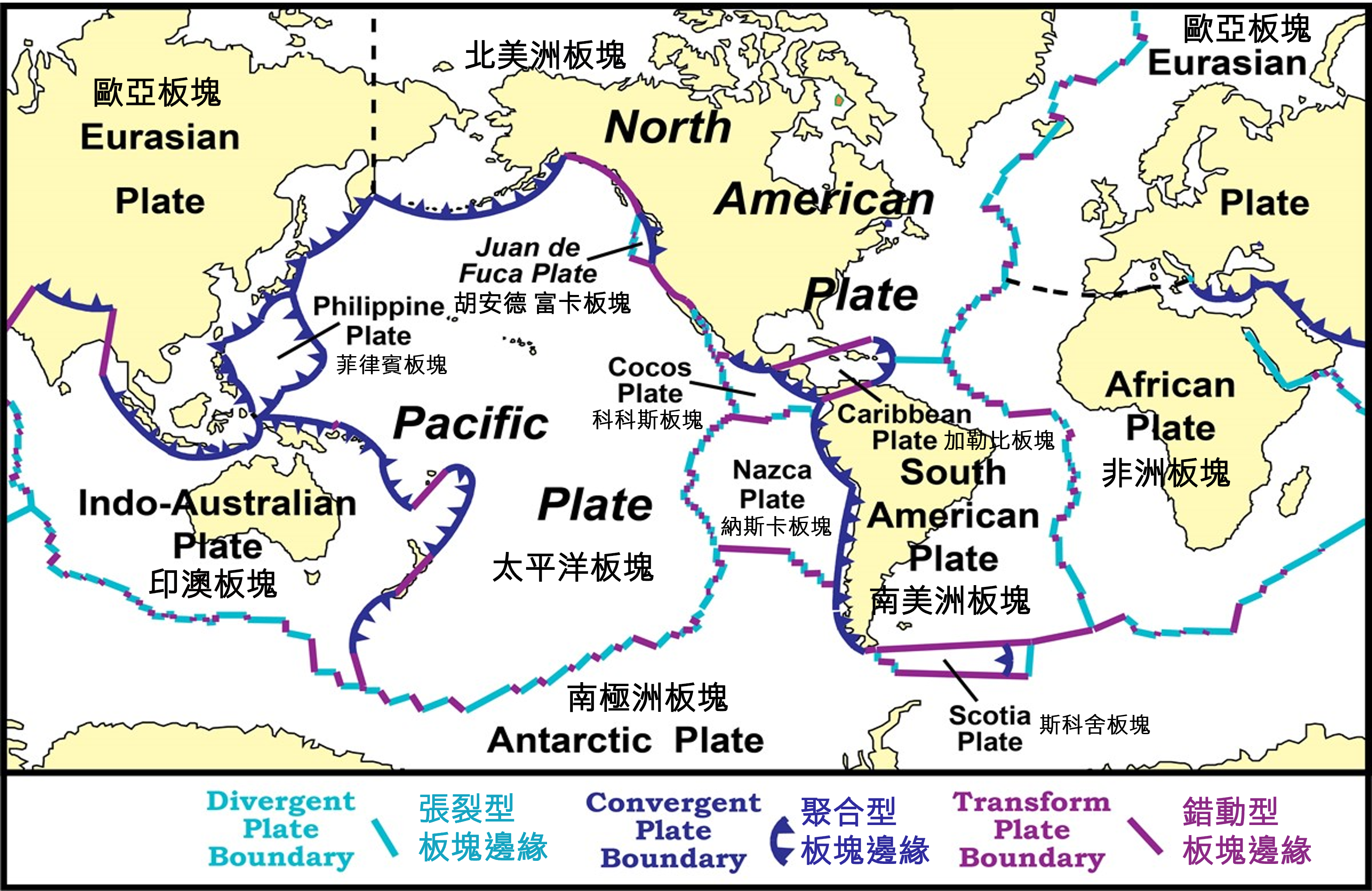

Earthquakes are caused by the movement of tectonic plates, which consist of the Earth’s crust and upper part of the mantle. These plates, varying in size and shape, form the surface of the Earth (Figure 1). While major earthquakes typically occur at plate boundaries, some can also occur along active faults within the plates, depending on factors including the fault dimension, geological structure and accumulated stress. In general, regions near plate boundaries experience earthquakes more frequently than intraplate areas. As a result, in the Pacific region, seismic activity is notably frequent in the Circum-Pacific seismic belt or the Ring of Fire, which spans regions such as the Solomon Islands, the Philippines, Japan and North America.

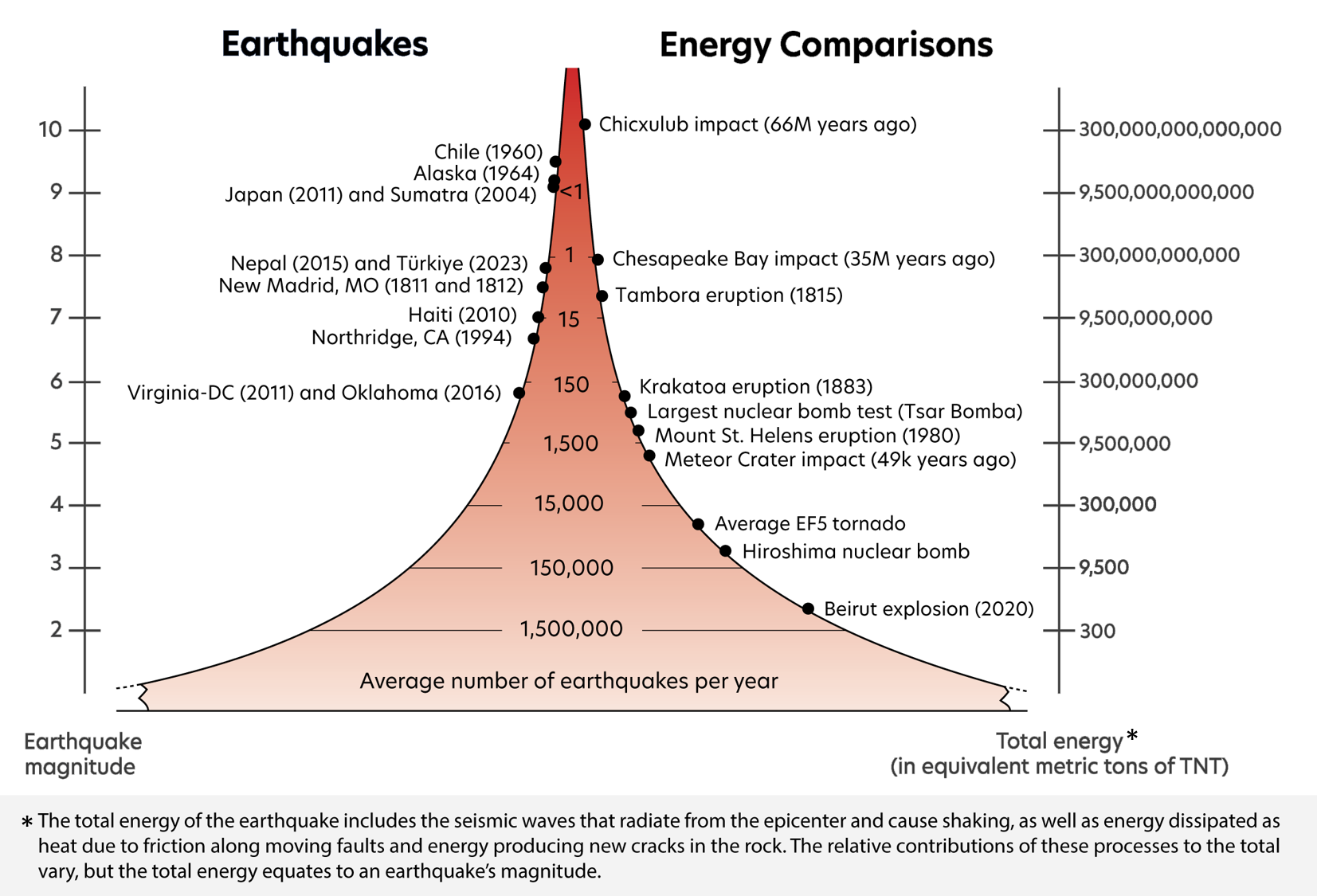

In fact, earthquakes occur somewhere in the world every day. The frequency of earthquakes decreases as magnitude increases (Figure 2). According to long-term historical records, the world experiences an average of 1,500 to 2,000 earthquakes of magnitude 5.0 or above, and around 150 to 200 of magnitude 6.0 or above each year. As for great earthquakes of magnitude 9.0 or above, they are rare and occur less than once a year on average.

Based on historical earthquake records, seismologists often use probability to express the likelihood of an earthquake of specific magnitude occurring within a certain geographical area and time frame. Generally, the larger the region or the longer the timeframe under consideration, the higher the probability will be. The “recurrence interval” is a statistical concept [3,4 ]. It refers to the estimated average period of the recurrence of earthquakes of a given magnitude in a specific region based on an assumed statistical distribution model. However, exceeding the return period does not mean an earthquake will definitely occur soon. It is also possible that an earthquake event will happen at a time shorter than the return period.

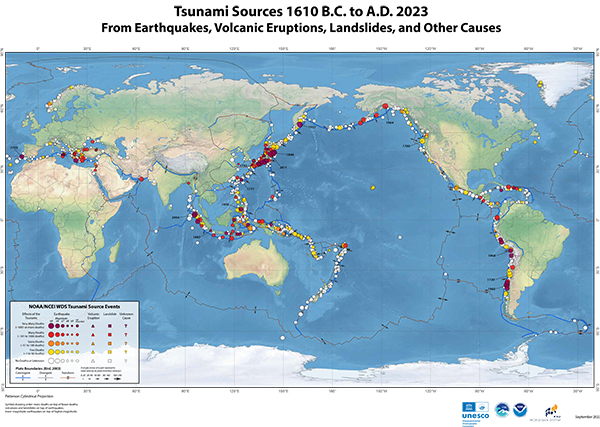

Around 80% of tsunamis are triggered by large submarine earthquakes. Other disturbances that can generate tsunamis include coastal and submarine landslides, volcanic eruptions, and even meteorite impacts, which are collectively referred to as non-seismic tsunamis (Figure 3). The Pacific Ocean is the most tsunami-prone region globally, accounting for about 70% of all recorded events. Due to blocking and diffraction effects of islands, tsunamis generated within the Pacific are generally weakened after entering the South China Sea. The height of tsunami triggered by an earthquake depends on various factors, including the earthquake magnitude, the location of epicentre, the focal depth, the rupture dimension, the fault displacement, as well as the fault strike, dip, and direction of fault displacement (i.e. focal mechanism).

2. Can Earthquakes and Tsunamis Be Predicted?

With current technology, the exact timing, location and magnitude of an earthquake cannot be predicted yet [6,7,8]. At present, seismologists can only calculate the probability of an earthquake of a certain magnitude or above occurring in a certain area within a certain period of time based on observational data over that area including historical earthquake events, geophysics, geochemistry and geological properties. They can also estimate the possible locations of future strong earthquakes and their corresponding possible maximum earthquake magnitude.

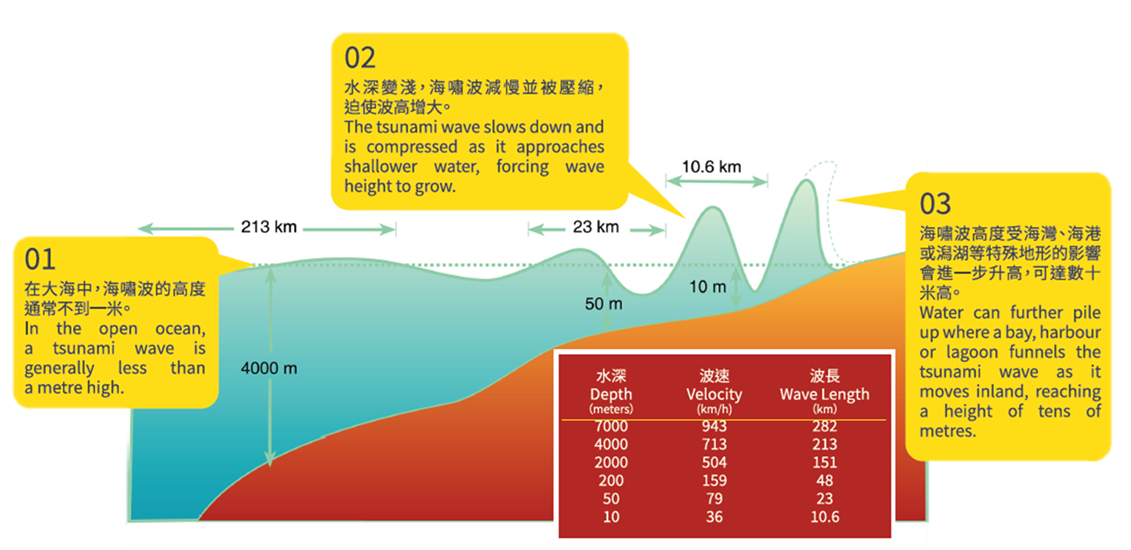

If a tsunami is triggered by a submarine or nearshore earthquake, we can use computer numerical simulations to predict the propagation time (travel time) and height of tsunami waves based on earthquake parameters including the location of hypocentre, magnitude, and focal mechanism. However, predicting non-seismic tsunamis, as mentioned earlier, is relatively difficult. Tsunami travel speed is closely related to the ocean depth. In the deep ocean with a water depth of around 5,000 meters, tsunami waves can travel at a speed of about 800 kilometers per hour (comparable to the speed of an international passenger aircraft). As these waves approach shallower coastal areas, their speed decreases while their wavelength is compressed, causing a significant increase in wave height (Figure 5).

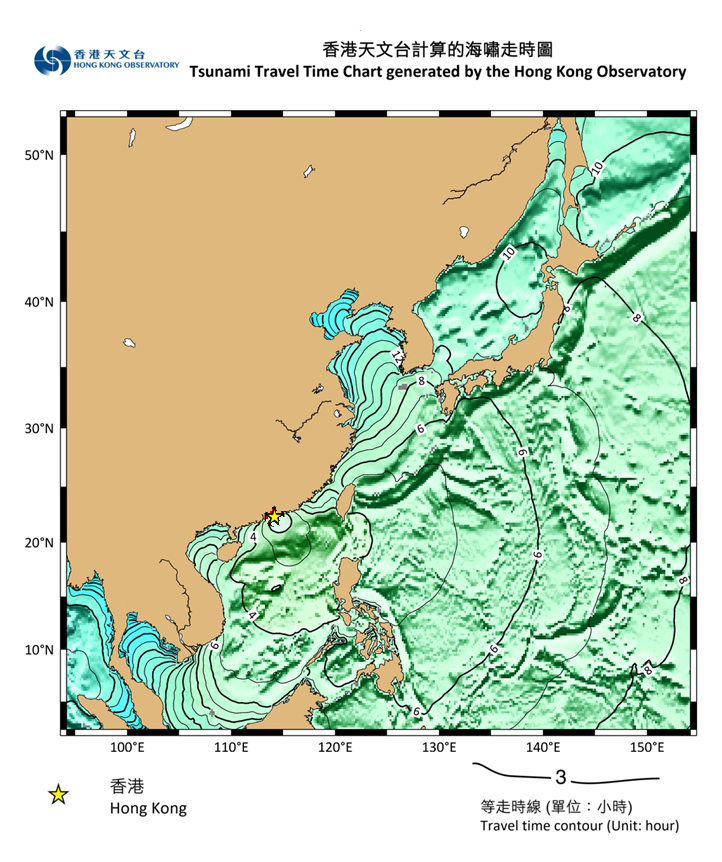

Although the more accurate tsunami wave travel times can only be calculated after obtaining the earthquake parameters, rough estimations can be made in advance. As the propagation speed of tsunami waves in the deep ocean is similar, the time required for waves to spread outwards from Hong Kong is similar to the time required for spreading from outside to Hong Kong. We can then roughly estimate the travel time of tsunami waves from any point in the ocean to Hong Kong. In the event of a tsunami, the time for the first wave of tsunami reaching Hong Kong can be roughly estimated from the travel time contours in Figure 6 by locating the tsunami source on the map. Tsunamis typically arrive as a series of waves, occurring every 5 to 60 minutes until the energy is completely dissipated.

3. Disaster Preparedness, Prevention and Response Measures for Earthquakes and Tsunamis

Before travelling abroad, it is important to understand the hazards and risks at your destination. Check hazard forecasts and warnings issued by local official agencies and download their relevant mobile applications that provide updates including earthquake, tsunami, and weather information (e.g. Japan[11]). Remember to note down the local emergency contact numbers, and familiarise yourself with the local government's alert systems, evacuation guidelines, and shelter arrangements. Upon arrival, locate the nearest evacuation routes and safe shelters as far as practicable.

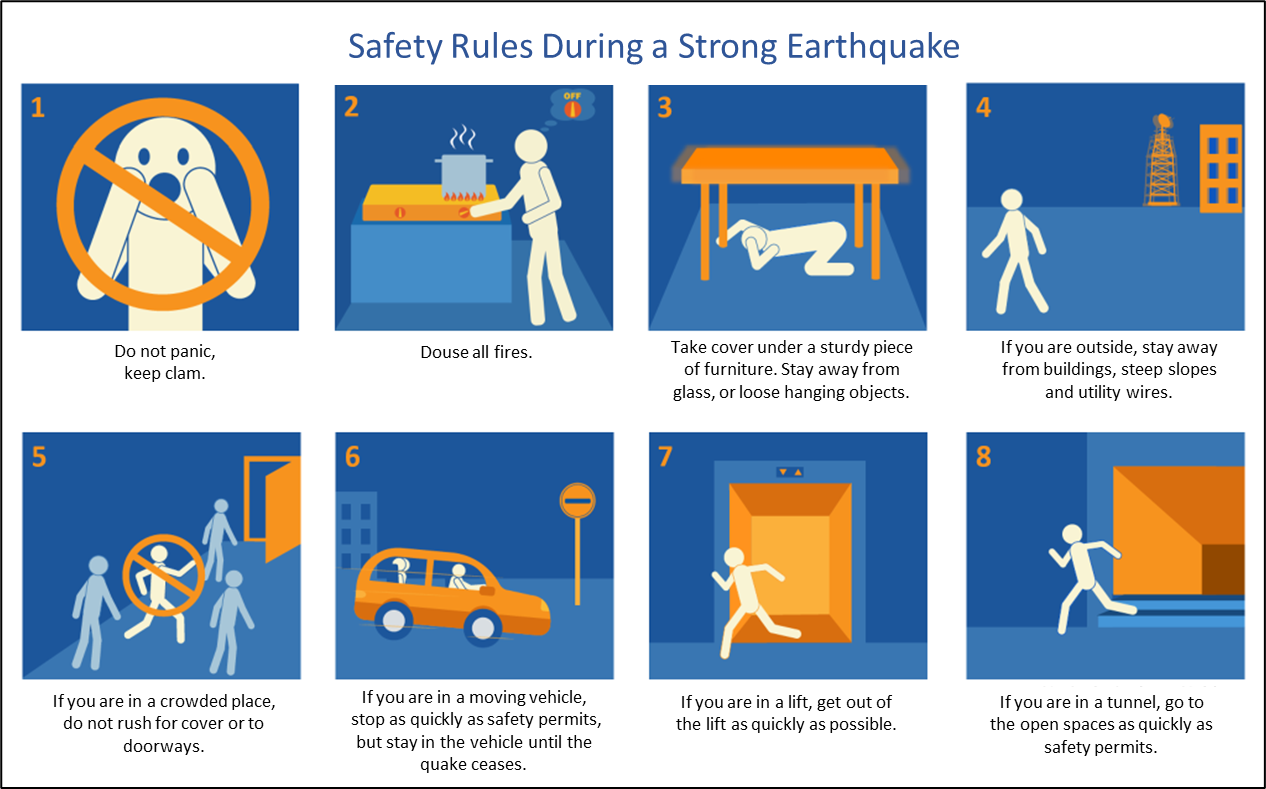

In the event of a strong earthquake (Figure 7), immediately “Drop, Cover, and Hold On”, move away from dangerous objects such as windows or hanging objects, stay calm, and avoid running, taking elevators, or jumping from buildings. If you are in a vehicle, safely pull over and remain inside until the earthquake is over. After the earthquake (Figure 8), ensure your own safety, inspect your surroundings, watch for secondary hazards, and follow local official guidance.

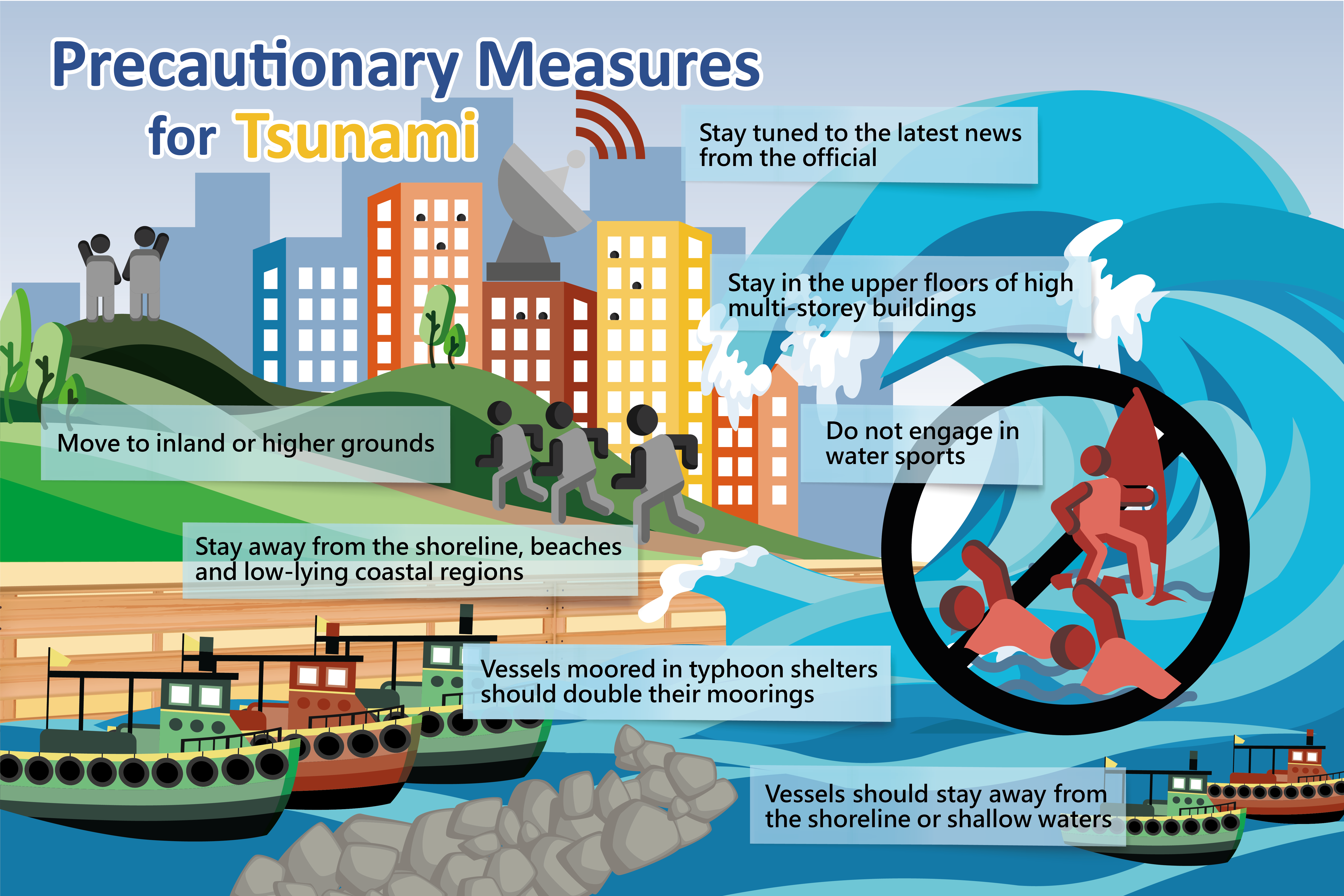

If you observe any of the following tsunami precursors, move away from the coastal or shallow waters to inland areas or higher ground as soon as possible. Those on land near the shore should seek shelter in high places or on the upper floors (above third level) of reinforced buildings. Do not wait for tsunami warning to take actions:

• Strong shaking felt near the shore due to an earthquake

• Unusual and rapid recession of seawater, exposing the seabed

• Sudden sea level anomalies pushing water inland (higher than normal tide levels)

• Unusual ocean whirlpools or roaring sounds coming from the sea

Tsunamis may strike repeatedly, so stay away from shores, beaches and low-lying coastal areas until the warning is officially lifted (Figure 9). Official warnings may be issued through a variety of channels including radio, mobile phone text messages, outdoor broadcasts, television announcements or telephone notifications. If you are caught by the wave, cling to sturdy objects (like trees or railings) or large floating items to stay afloat. If you are in a low-risk area, you should follow official guidelines and avoid moving on your own. After a tsunami occurs, you still need to stay alert and pay attention to environmental safety, avoid wading and approaching collapsed power lines or water-clogged areas[12].

In summary, the exact occurrence time, location, and magnitude of earthquakes cannot be predicted, but what we can do is: Don’t panic, acquire relevant knowledge and information, make good disaster prevention preparations, and learn how to respond to hazards appropriately.

References:

[1] National Park Service: Evidence of Plate Motions

[2] EarthScope: How Often Do Earthquake Occur? (Last updated on 15 April, 2025)

[3] HKO Educational Resources: Return Period: “Once in N Years”?

[4] United States Geological Survey (USGS): Earthquake Hazards Program

[5] International Tsunami Information Centre (ITIC): Global and Regional Hazard Maps

[6] Video containing message from the Director-General of Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA) on earthquake prediction (in Japanese but with English subtitles)

[7]United States Geological Survey (USGS): Can You Predict Earthquakes?

[8] HKO Educational Resources: Can Earthquakes be Predicted?

[9] HKO Educational Resources: How to Interpret Seismic Parameters?

[10] International Tsunami Information Centre (ITIC): Tsunami Wave Characteristics

[11] Japan Tourism Agency

[12] Hong Kong Red Cross: Disaster Preparedness Knowledge