Fujiwhara effect

19 November 2010

When tropical cyclones come near each other, we often can observe on satellite pictures that they rotate against each other in a counter-clockwise direction. The phenomenon is known as the Fujiwhara effect, named after Dr. Sakuhei Fujiwhara (1884-1950) who described it in a 1921 paper about the motion of vortices in water. He later became the director of the Japan Meteorological Agency in 1941.

The effect is evident when the two storms come within about 1,000 kilometres of each other. They tend to rotate about a point between them. Normally, the larger storm tends to dominate the interaction, and the smaller one will orbit around it and sometimes become swallowed up by it.

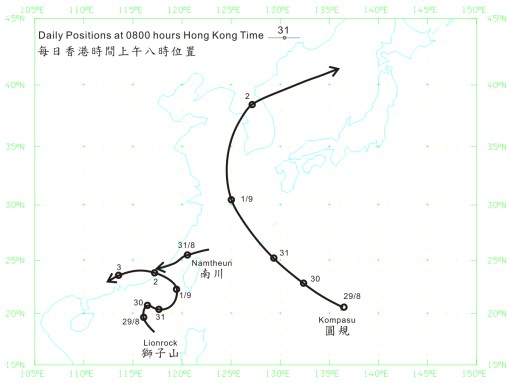

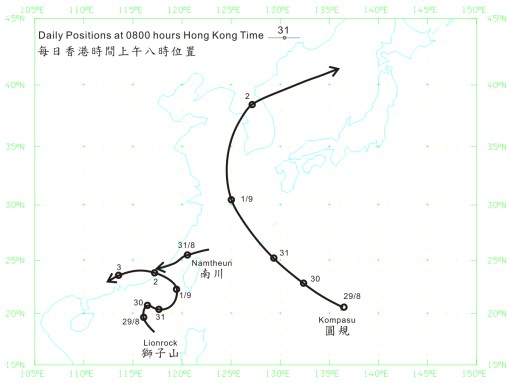

Examples of the Fujiwhara effect are abundant in this part of the world. The recent case in late August and early September is an interesting one involving not two, but three storms, namely Lionrock, Kompasu and Namtheun (Figure 1).

Figure 1Tracks of three tropical cyclones, Lionrock, Kompasu and Namtheun

during late August to early September, 2010

Lionrock formed over the South China Sea to the south-southeast of Hong Kong on 28 August, moving northwestwards. This was followed by Kompasu, which formed over the western North Pacific to the southeast of Okinawa the next day. Kompasu then sped towards the northwest, while Lionrock started to move eastward.

Meantime, Namtheun formed northeast of Taibei/Taipei on 30 August, between the two storms. It was short-lived, moving southwestward over the next day or so, before being absorbed into the circulation of Lionrock on 1 September.

![Figure 2 Infrared satellite image showing the three tropical cyclones, Lionrock, Namtheun and Kompasu at 8 p.m. on 31 August 2010. [The satellite imagery was originally captured by Multi-functional Transport Satellite-2 (MTSAT-2) of Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).]](/en/blog/images/20101119_fig2.jpg)

Figure 2Infrared satellite image showing the three tropical cyclones, Lionrock,

Namtheun and Kompasu at 8 p.m. on 31 August 2010.

[The satellite imagery was originally captured by Multi-functional

Transport Satellite-2 (MTSAT-2) of Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).]

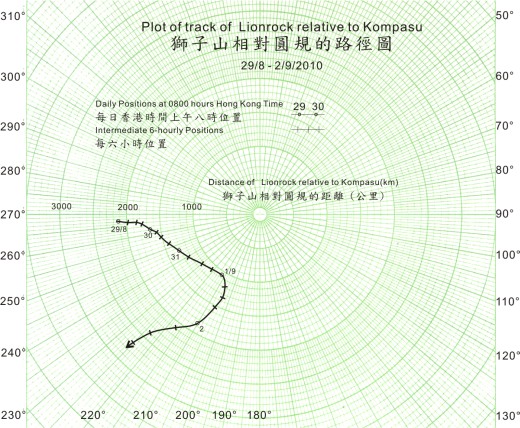

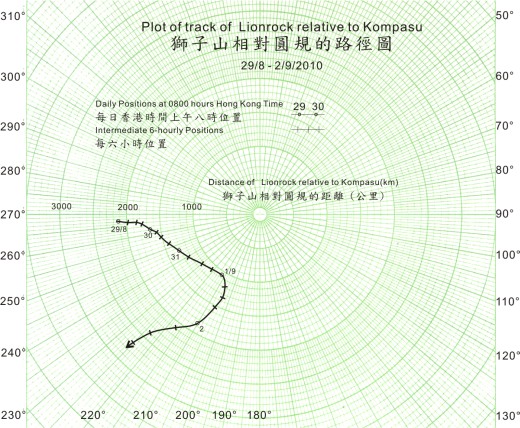

On the satellite image (Figure 2), Kompasu had the largest size and appeared to dominate the interaction with the other two storms, Lionrock and Namtheun. A plot of Lionrock's movement relative to Kompasu (i.e. with Kompasu held stationary at the centre) is given in Figure 3, which shows that, before 1 September, Lionrock indeed moved generally counter-clockwise relative to Kompasu as the two moved closer to each other to within a separation of slightly over 1000 km or so. After this, the two started to move away from each other under the influence of background steering flow.

Figure 3Plot of track of Lionrock relative to Kompasu

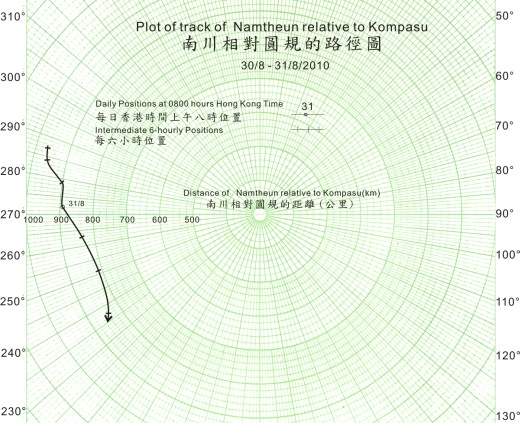

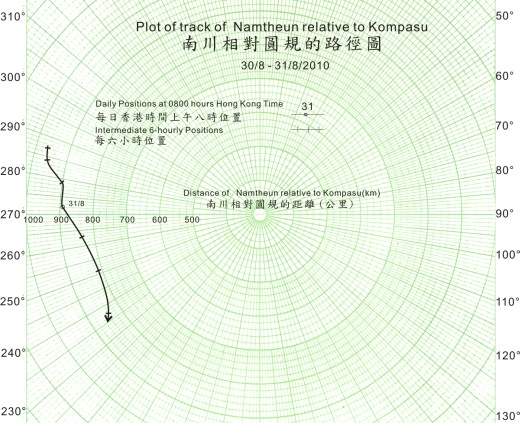

The same counter-clockwise movement can be observed on Namtheun's movement relative to Kompasu, as evident in Figure 4. Namtheun also exhibited a similar, but no so clear-cut, movement relative to Lionrock (not shown).

Figure 4Plot of track of Namtheun relative to Kompasu

The interaction of three storms is complex and still poses a challenge to numerical weather prediction models in accurately forecasting their future movement.

We know that in the Southern Hemisphere, winds around a tropical cyclone flow in a direction opposite to those in the Northern Hemisphere. Could you figure out which direction would two storms in the Southern Hemisphere rotate against each other --- clockwise or counter-clockwise?

B.Y. Lee and W.H. Lui

The effect is evident when the two storms come within about 1,000 kilometres of each other. They tend to rotate about a point between them. Normally, the larger storm tends to dominate the interaction, and the smaller one will orbit around it and sometimes become swallowed up by it.

Examples of the Fujiwhara effect are abundant in this part of the world. The recent case in late August and early September is an interesting one involving not two, but three storms, namely Lionrock, Kompasu and Namtheun (Figure 1).

Figure 1Tracks of three tropical cyclones, Lionrock, Kompasu and Namtheun

during late August to early September, 2010

Lionrock formed over the South China Sea to the south-southeast of Hong Kong on 28 August, moving northwestwards. This was followed by Kompasu, which formed over the western North Pacific to the southeast of Okinawa the next day. Kompasu then sped towards the northwest, while Lionrock started to move eastward.

Meantime, Namtheun formed northeast of Taibei/Taipei on 30 August, between the two storms. It was short-lived, moving southwestward over the next day or so, before being absorbed into the circulation of Lionrock on 1 September.

![Figure 2 Infrared satellite image showing the three tropical cyclones, Lionrock, Namtheun and Kompasu at 8 p.m. on 31 August 2010. [The satellite imagery was originally captured by Multi-functional Transport Satellite-2 (MTSAT-2) of Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).]](/en/blog/images/20101119_fig2.jpg)

Figure 2Infrared satellite image showing the three tropical cyclones, Lionrock,

Namtheun and Kompasu at 8 p.m. on 31 August 2010.

[The satellite imagery was originally captured by Multi-functional

Transport Satellite-2 (MTSAT-2) of Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).]

On the satellite image (Figure 2), Kompasu had the largest size and appeared to dominate the interaction with the other two storms, Lionrock and Namtheun. A plot of Lionrock's movement relative to Kompasu (i.e. with Kompasu held stationary at the centre) is given in Figure 3, which shows that, before 1 September, Lionrock indeed moved generally counter-clockwise relative to Kompasu as the two moved closer to each other to within a separation of slightly over 1000 km or so. After this, the two started to move away from each other under the influence of background steering flow.

Figure 3Plot of track of Lionrock relative to Kompasu

The same counter-clockwise movement can be observed on Namtheun's movement relative to Kompasu, as evident in Figure 4. Namtheun also exhibited a similar, but no so clear-cut, movement relative to Lionrock (not shown).

Figure 4Plot of track of Namtheun relative to Kompasu

The interaction of three storms is complex and still poses a challenge to numerical weather prediction models in accurately forecasting their future movement.

We know that in the Southern Hemisphere, winds around a tropical cyclone flow in a direction opposite to those in the Northern Hemisphere. Could you figure out which direction would two storms in the Southern Hemisphere rotate against each other --- clockwise or counter-clockwise?

B.Y. Lee and W.H. Lui