Applications of Artificial Intelligence Models in Weather Forecasting

Applications of Artificial Intelligence Models in Weather Forecasting

LAI Sin-ki

December 2025

Numerical Weather Prediction (NWP) is crucial for contemporary meteorological services. The Observatory makes reference to a series of NWP models when preparing weather forecasts. NWP models divide the three-dimensional space of Earth's atmosphere into grid points. Taking observational data from various sources (including ground stations, satellites and radars), NWP models use high-performance computers to calculate the evolution of a series of meteorological elements (such as wind speed, temperature, air pressure, relative humidity) over time at each grid point, enabling the prediction of future weather conditions. Traditional NWP models solve equations based on principles of atmospheric physics and dynamics. Their computational tasks are expensive and time-consuming. In addition, the current scientific understanding and description of physical processes of many weather phenomena remains inadequate, especially for rapidly changing and localized events like severe convections and rainstorms. The NWP model equations often require to adopt certain approximations or simplifications. Due to the chaotic nature of the atmosphere, along with errors in observations and approximations in numerical equations, there are inherent inaccuracies in the predictions of the NWP models and these inaccuracies will increase with the forecast time.

In recent years, rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) has provided new opportunities for weather prediction. AI weather prediction models do not directly solve physical equations. Instead, they use deep learning with vast amounts of long-term global meteorological data. This allows AI weather prediction models to grasp the evolution patterns of weather systems and predict future changes (Figure 1). For details on the principles of AI models, please refer to the article "Weather Forecast Based on Artificial Intelligence”.

Figure 1 The schematic on the left illustrates that weather prediction models take numerous observational data to calculate various weather elements on grid points of Earth’s atmosphere. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence models use decades of meteorological data for deep learning, subsequently a series of objective forecasting products can be produced.

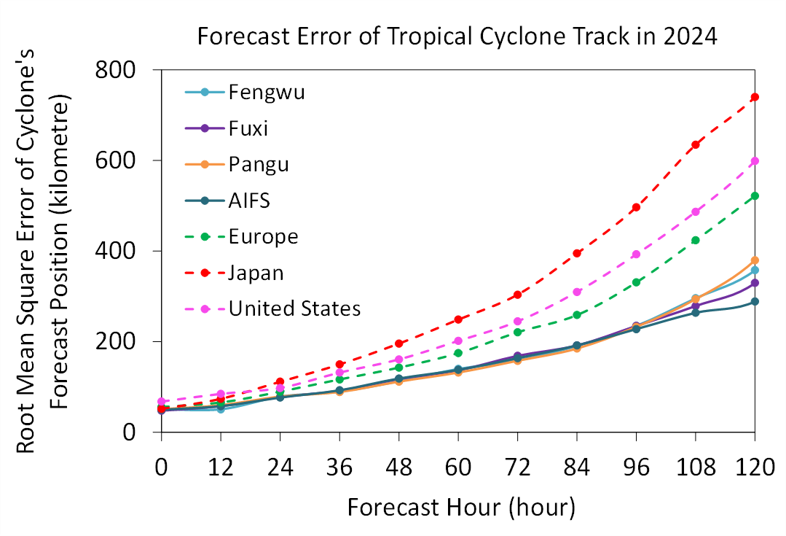

AI models can now predict the evolution of large-scale weather systems with considerable accuracy. According to the Observatory's verification on weather prediction models in 2024, the performance of various AI models in forecasting large-scale weather patterns over the next 10 days has already reached a level similar to or even slightly surpassed that of traditional models. Additionally, in medium-range forecasts for tropical cyclone tracks, the overall performance of AI models has exceeded that of traditional models. A summary of forecast track errors for tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific and the South China Sea in 2024 (Figure 2) indicates that the mean errors of AI models (solid lines) are generally smaller than those of traditional models (dashed lines). However, it is noteworthy that the average error for the fifth-day forecast of tropical cyclone track by AI models is still as high as 300 to 400 kilometres, which can lead to significantly different impacts in a specific region.

Figure 2 Forecast performance of various models on the track of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific and the South China Sea in 2024. AI models are denoted by solid lines; traditional models by dashed lines. The mean forecast errors of AI models on tropical cyclones track are generally smaller than those of traditional models across forecast hours.

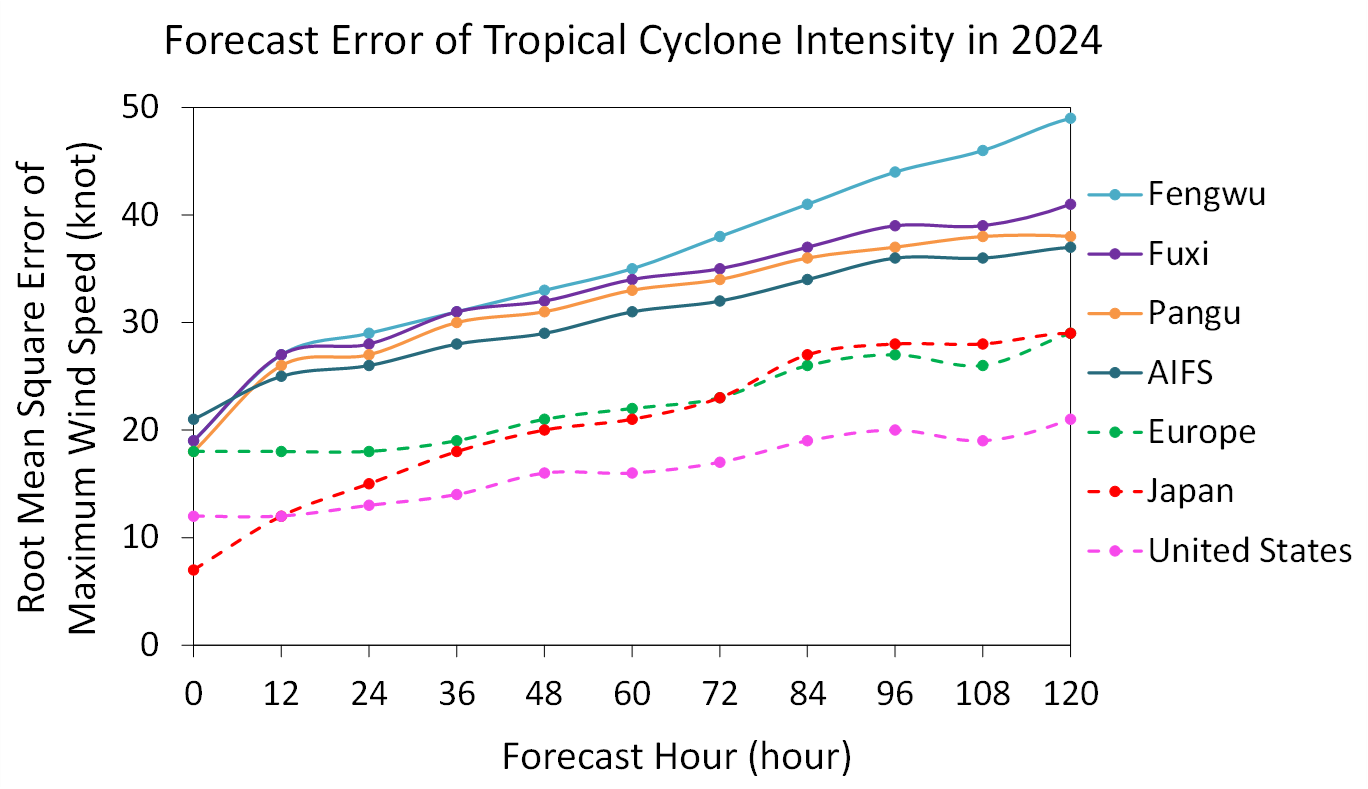

Current limitations of AI models stem from the quality and resolution of training data, as well as the training strategies and algorithms used. Current AI models still face considerable limitations, particularly for meso-scale and small-scale weather systems. For instance, the spatial and temporal resolutions of AI models are still not as fine as those of traditional models; most AI models can only provide predictions of limited meteorological elements such as wind, temperature, and pressure. Even though some recent AI models offer rainfall predictions, many aspects of heavy rainfall events, including precise timing, location, and rainfall amount, remain elusive. Furthermore, for mature tropical cyclones, AI models tend to underestimate their intensity (Figure 3). As for extreme weather events, which occur rarely in historical records and may not even be present in the training dataset, the capability of AI models for predicting such events still requires further verification.

Figure 3 Forecast performance of various models on the intensity of tropical cyclones over the western North Pacific and the South China Sea in 2024. AI models are denoted by solid lines; traditional models by dashed lines. The forecast errors of AI models on tropical cyclones intensity are generally larger than those of traditional models across forecast hours.

Since mid-2023, the Observatory has been running a series of AI weather prediction models in real time, including "Fengwu"[1], "Fuxi"[2], "Pangu"[3], “AIFS”[4], etc. The Observatory uses the model outputs to produce a series of objective forecasting products, such as prognostic charts displaying large-scale weather patterns, tropical cyclone tracks, time series of local temperatures and wind speeds, etc. The model biases are also corrected based on their past performance through statistical and machine learning methods.

In daily operations, forecasters refer to the results of multiple traditional and AI models. As it is common to have discrepancies among different models, forecasters consider various factors such as models’ past performance, stability, and alignment with actual observational data, along with forecasting experience under similar weather situations in the past, to comprehensively assess which models’ forecast scenarios and outcomes are more aligned with the weather situation. Forecasters also take into account local topography and climate characteristics to make appropriate adjustments to the forecasting products.

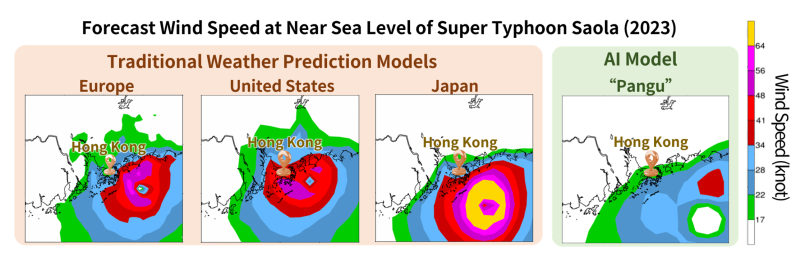

Tropical cyclone forecasting is a good example illustrating the two types of models complementing each other: AI models often perform better in predicting tracks, effectively reducing forecast position errors, while traditional models still demonstrate advantages over intensity forecasts and wind distribution. Using Super Typhoon Saola that struck Hong Kong in 2023 as an example, the associated storm to hurricane force winds affected many areas of the territory. Traditional models generally predicted that Saola would bring winds of storm to hurricane force, while AI model "Pangu" significantly underestimated its wind strength (Figure 4). Depending on the situation, the Observatory will flexibly utilize outputs from both traditional and AI models to improve the overall forecast accuracy for various weather systems across different temporal and spatial scales.

Figure 4 Forecast wind speed at near sea level of Super Typhoon Saola (2023) in the vicinity of Hong Kong by various models. Traditional models from Europe, United States and Japan forecast Saola having winds up to storm (purple-coloured) to hurricane (amber-coloured) force; while that from AI model “Pangu” were only up to strong (blue-coloured) to gale (red-coloured) force.

Although the application of AI models is still in its early stage, their rapid development shows great potential for weather forecasting. Looking ahead, improving the quality and resolution of training data is expected to enhance AI models' ability to predict meso-scale and small-scale weather systems and expand the range of predictable meteorological elements. The Observatory will continue to validate the performance of AI models and actively promote their application in operations. We will also collaborate with universities and research institutions to further enhance various models’ capabilities, and strive to provide more accurate and timely weather information.

References:

[1] Han, T., Guo, S., Ling, F. et al. FengWu-GHR: Learning the kilometer-scale medium-range global weather forecasting.

[2] Chen, L., Zhong, X., Zhang, F. et al. FuXi: A cascade machine learning forecasting system for 15-day global weather forecast. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 190 (2023).

[3] Bi, K., Xie, L., Zhang, H. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533–538 (2023).

[4] Lang, Simon et al., AIFS-ECMWF's data-driven forecasting system. arXiv:2406.01465 (2024).

[1] Han, T., Guo, S., Ling, F. et al. FengWu-GHR: Learning the kilometer-scale medium-range global weather forecasting.

[2] Chen, L., Zhong, X., Zhang, F. et al. FuXi: A cascade machine learning forecasting system for 15-day global weather forecast. npj Clim Atmos Sci 6, 190 (2023).

[3] Bi, K., Xie, L., Zhang, H. et al. Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks. Nature 619, 533–538 (2023).

[4] Lang, Simon et al., AIFS-ECMWF's data-driven forecasting system. arXiv:2406.01465 (2024).